How do low-carbohydrate diets affect blood glucose levels?

Good morning! Today we have a new blog to help you understand how our body works and how blood glucose levels behave with low-carb diets. Low-carb diets have become quite popular, both among people with obesity to lose weight and improve associated symptoms, and in the general population as a healthy lifestyle choice.

But what does a low-carb diet entail? A low-carb diet, also known as a low-carb diet, is one where carbohydrate intake is reduced, consuming less than 130 grams per day, providing only 26% of daily energy from carbohydrates. The rest of the calories come from fats and proteins (1). Clearly, the impact of this diet on blood glucose levels differs from that of a high-carb diet.

Low-carb diet

When carbohydrate (carb) intake is restricted for a prolonged period, the body starts to use some of its glycogen reserves to keep blood glucose levels stable (remember that glycogen is the form in which carbohydrates are stored in the liver and muscles). Glycogen reserves are relatively small, storing about 70-100 grams in the liver and around 400 grams in the muscles. Most of these glycogen reserves are significantly depleted within 48 hours following complete carbohydrate restriction (especially those in the liver), but full depletion can take longer, depending on the amount of carbs consumed and daily energy expenditure.

Once glycogen reserves are exhausted, the body begins to increase the mobilization of fats to meet most of its energy demands. Gluconeogenesis (the process by which glucose is produced from fats or amino acids) is enhanced to ensure a sufficient amount of circulating glucose for the central nervous system and red blood cells. Fatty acids released into the blood can be oxidized by the liver and muscles to produce energy. Fatty acids can also be partially oxidized by the liver to create ketone bodies, which are then used as fuel (2).

Consequences on blood glucose and insulin response

Low-carbohydrate diets have been shown, in the short term, to decrease fasting blood glucose levels and plasma glucose after 24 hours. However, long-term studies have concluded that differences in these glucose levels compared to diets with higher carbohydrate content are insignificant. It’s not only the amount of carbohydrates ingested that matters but also the type. High glycemic index carbohydrates, such as bread, refined cereals, sugar, and sweets, increase blood glucose more easily. In contrast, low glycemic index carbohydrates, such as whole grains, legumes, and full-fat dairy products, help maintain glucose levels within an appropriate range. Nonetheless, this factor depends on each person’s metabolism, meaning that the glycemic response of an elite athlete will differ from that of a sedentary person with the same intake.

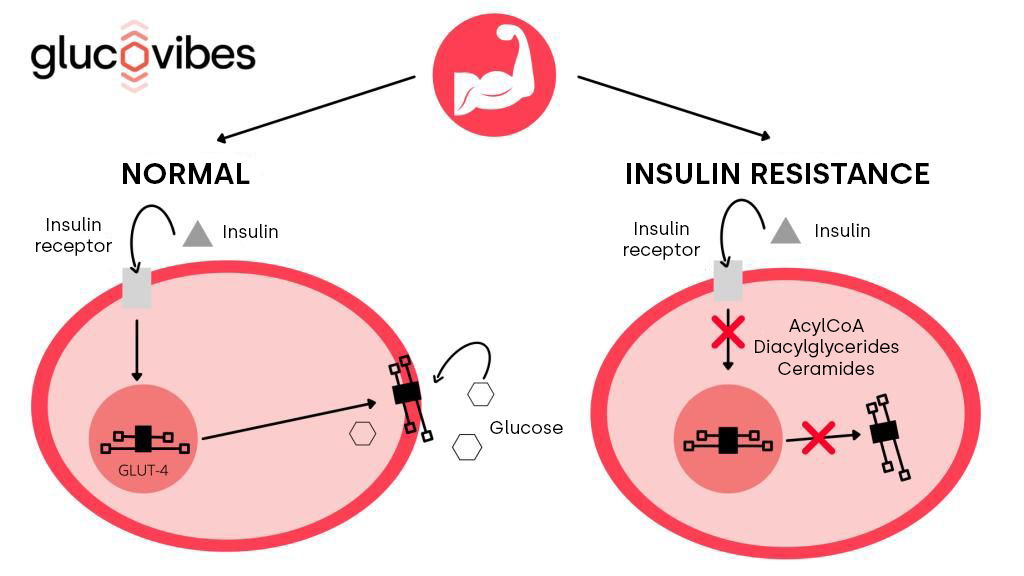

This type of diet also leads to a reduction in circulating insulin levels, which promotes the release of fatty acids. The elevation of these levels promotes their utilization as fuel by the muscles, which drives fat loss. As these diets involve higher fat intake, long-term insulin sensitivity may be negatively affected.

Several studies support the hypothesis that alterations in fatty acid metabolism contribute to insulin resistance due to changes in fat distribution between adipocytes (fat-storing cells) and muscle or liver. This shift leads to the accumulation of fatty acids in these insulin-sensitive tissues, contributing to insulin resistance and, consequently, reduced glucose transport.

Restriction of carbohydrates in athletes

In recent decades, the importance of nutrition for recovery and athletic performance has been well-established, with a particular focus on the role of carbohydrates (5). When engaging in high-intensity exercise, carbohydrates become the primary energy source, making glycogen depletion a limiting factor for performance (6). Low availability of carbohydrates from the diet during exercise impairs performance maintenance due to the depletion of stored hepatic glycogen. This, in turn, worsens the glycemic response, impacting the athlete’s ability to maintain high exercise intensity and thus creating a greater metabolic load. This latter factor negatively affects post-exercise recovery.

So, what happens in the body when you don’t consume enough carbohydrates? When carbohydrate availability is low, the liver produces ketones to use as energy, as mentioned earlier. Fatigue during high-intensity, short-duration exercise causes acidosis (an imbalance between acid and base). Adding ketone-induced acidosis further inhibits muscle contractile function, leading to reduced performance, poorer recovery, and increased muscle fatigue (7).

For this reason, to achieve high performance levels during exercises that rely on the glycolytic pathway (whether endurance or strength exercises), it is advisable to start exercise with glycogen stores significantly full and to continuously supply carbohydrates during exertion.

Conclusions

A low-carb diet is a type of diet where carbohydrate intake is reduced to less than 130g per day. Short-term studies have shown that such diets decrease fasting blood glucose levels and plasma glucose after 24 hours. However, no significant differences have been observed compared to high-carb diets in the long term. Additionally, these diets involve a high intake of fats, which can lead to defects in insulin signaling, insulin resistance, and decreased glucose transport. Thus, we conclude that a low-carb diet may not be the most suitable for athletic performance.

References

- [1] Bilsborough SA, Crowe TC. Low-carbohydrate diets: what are the potential short- and long-term health implications? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2003; 12: 396–404.

- [2] Adam-Perrot A, Clifton P, Brouns F. Low-carbohydrate diets: nutritional and physiological aspects. Obes Rev. 2006 Feb;7(1):49-58.

- [3] Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Stein TP. Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Mar 15;142(6):403-11.

- [4] MS Wolever T, Mehling C. Long-term effect of varying the source or amount of dietary carbohydrate on postprandial plasma glucose, insulin, triacylglycerol, and free fatty acid concentrations in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003 Mar;77(3):612-621.

- [5] Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and Athletic Performance. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Mar;116(3):501-528.

- [6] Noakes TD. Physiological models to understand exercise fatigue and the adaptations that predict or enhance athletic performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000 Jun;10(3):123-45.

- [7] Wroble KA, Trott MN, Schweitzer GG, Rahman RS, Kelly PV, Weiss EP. Low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet impairs anaerobic exercise performance in exercise-trained women and men: a randomized-sequence crossover trial. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019 Apr;59(4):600-607.