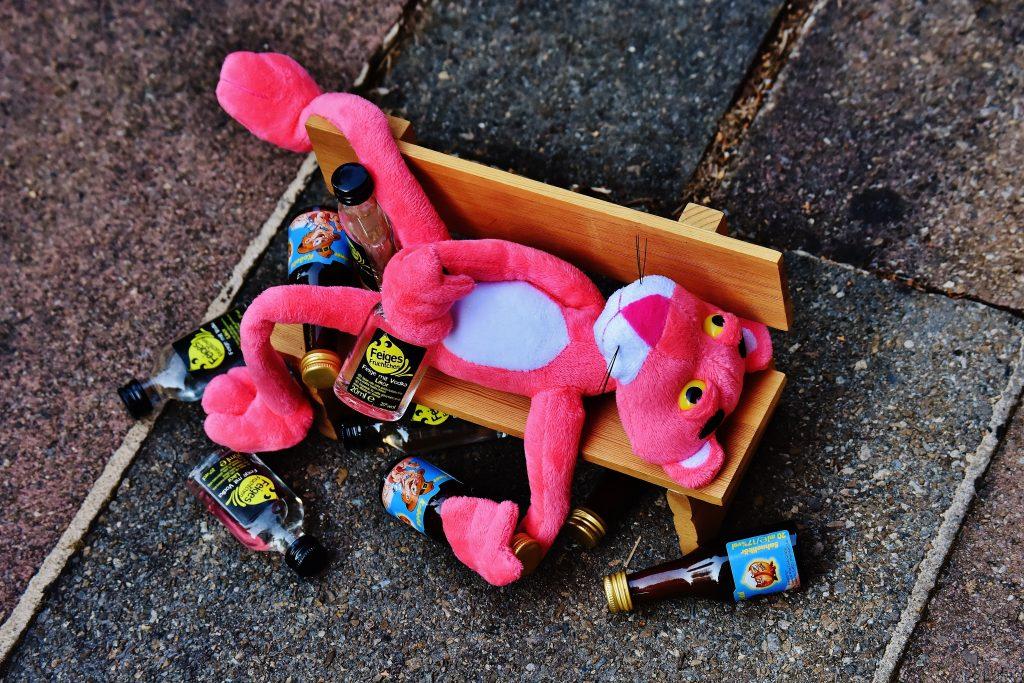

How alcohol really affects our body

Currently, alcohol consumption is considered a socially acceptable practice and is recognized as a means of socialization (1). However, we want to reflect on how alcohol truly affects our body. Alcohol consumption is a public health issue that requires immediate preventive actions. Excessive intake can lead to non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular conditions, liver cirrhosis, and various types of cancer. Therefore, it is common for people to abuse such beverages without considering the potential impact on their health.

Alcohol

Alcohol is primarily absorbed through the small intestine, with only about 10% absorbed in the stomach. Absorption begins within 10 minutes after consumption, and peak blood concentration is reached between 30 and 90 minutes. Considering that a standard drink contains between 10 and 12 grams of ethanol and that 90% of the absorbed alcohol is metabolized in the liver, alcohol consumption that exceeds the rate of oxidation results in accumulation in the body and induces symptoms of intoxication. Alcohol has the potential to affect almost all organs, with the main adverse effects being neurological, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and respiratory (2).

Neurologically, alcohol is a central nervous system depressant, meaning it slows down brain activity. It can alter mood, behavior, and self-control, impair memory, and affect clear thinking. It also impacts coordination and physical control.

🥃 Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant; it can impair memory, irritate the mucosa of the esophagus and stomach, and affect gluconeogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in the liver.

Gastrointestinally, alcohol can irritate the mucosa of the esophagus and stomach, leading to esophagitis, gastritis, and gastric ulcers. High concentrations of alcohol can cause stomach spasms, resulting in nausea and vomiting or inflammation of the pancreas, which can lead to acute pancreatitis. Additionally, alcohol affects gluconeogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in the liver, leading to fat accumulation in liver cells, which can present as fatty liver. Repeated episodes of excessive alcohol consumption often result in alcoholic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis (3).

Alcohol and glucose metabolism

The effects of alcohol on carbohydrate metabolism are complex and not fully understood. Some effects are directly related to the influence of alcohol or its metabolic products, acetaldehyde and acetate, while others are associated with an increase induced by the NADH/NAD ratio in liver cells. This process, known as redox shift, results from the oxidation of alcohol to acetaldehyde and acetaldehyde to acetate by dehydrogenases.

The consequence of this shift is the inhibition of the citric acid cycle and β-oxidation of fatty acids, while the conversion of pyruvate to lactate is favored. The increased NADH/NAD ratio and lactate/pyruvate ratio contribute to the inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Therefore, after the consumption of 48 grams of alcohol (approximately 4 standard drinks), hepatic gluconeogenesis decreases by about 45% (2,4).

If glycogen stores are normal, hepatic glucose production decreases by 12% after moderate alcohol consumption, which rarely leads to hypoglycemia. However, when glycogen reserves are depleted, normal blood glucose levels cannot be maintained, potentially resulting in hypoglycemia. This depletion is not limited to malnourished alcoholics but can also occur in individuals on a low-carbohydrate diet or those fasting who skip one or two meals while drinking (2,4).

Alcohol and sports performance

Athletes, like the general population, often consume alcohol. The detrimental effects of alcohol on human physiology are well-documented, as acute alcohol ingestion affects many aspects of metabolism, neural function, cardiovascular physiology, thermoregulation, and skeletal muscle myopathy. However, its impact on exercise performance is less detailed (5).

Alcohol has harmful effects on skeletal muscle by inhibiting Ca2+ transients in myocytes through the inhibition of sarcolemmal Ca2+ channels. As a result, this impairs excitation-contraction coupling, reducing force production. Its effects on hydration and diuretic function are also well-known. Alcohol inhibits antidiuretic hormone (ADH) due to ethanol. Additionally, alcohol has been shown to act as a peripheral vasodilator, presenting several complications:

- Firstly, it increases fluid loss through evaporation, exacerbating dehydration that may already exist from sports activities.

- Secondly, it interferes with central thermoregulation mechanisms, causing a reduction in central body temperature. Therefore, alcohol consumption has been repeatedly shown to decrease work tolerance in both high and low ambient temperatures (6).

Aside from being a readily available energy source (7 kcal per gram), alcohol has several effects on human metabolism. As previously mentioned, high doses of alcohol affect hepatic gluconeogenesis and subsequent glucose production, decrease the uptake of gluconeogenic precursors like lactate and glycerol, and reduce the uptake and storage of muscle glycogen. There is a threshold at which alcohol becomes detrimental to both aerobic and anaerobic performance. Cofan et al. describe an alcohol intoxication threshold of 20 mmol/L of ethanol in both animal and human studies, beyond which performance reduction becomes significant (7).

In conclusion, occasional or moderately low alcohol consumption does not show any proven harmful effects. However, chronic and moderately high consumption has severe consequences, not only on cardiovascular health but also in the development of certain types of cancers and liver diseases. Consuming an average of 4 drinks with low glycogen levels can inhibit gluconeogenesis and lead to hypoglycemia. Additionally, the detrimental effects of alcohol consumption are even more pronounced in athletes, as it directly impacts athletic performance and recovery.

Still have questions about these effects? At Glucovibes, we provide personalized and detailed analyses on how every aspect of your diet, along with other daily factors such as exercise, sleep, and stress, affects you. Try Glucovibes today!

References

- [1] Ahumada-Cortez J. G., Gámez-Medina M. E., Valdez-Montero C. El consumo de alcohol como problema de salud pública. Ra Ximhai. 2017; 13(2), 13-24.

- [2] Van de Wiel A. Diabetes mellitus and alcohol. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20(4):263-7.

- [3] Jung YC, Namkoong K. Alcohol: intoxication and poisoning – diagnosis and treatment. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;125:115-21.

- [4] Siler SQ, Neese RA, Christiansen MP, Hellerstein MK. The inhibition of gluconeogenesis following alcohol in humans. Am J Physiol 1998; 275: 897–907.

- [5] Barnes MJ. Alcohol: impact on sports performance and recovery in male athletes. Sports Med. 2014 Jul;44(7):909-19.

- [6] Vella LD, Cameron-Smith D. Alcohol, athletic performance and recovery. Nutrients. 2010 Aug;2(8):781-9.

- [7] Cofán M, Nicolás JM, Fernández-Solà J, Robert J, Tobías E, Sacanella E, Estruch R, Urbano-Márquez A. Acute ethanol treatment decreases intracellular calcium-ion transients in mouse single skeletal muscle fibers in vitro. Alcohol. 2000;35(2):134-8.