How does the menstrual cycle affect my glucose?

Do you feel hungrier before your period? Are you more tired? Do you crave greasy and sugary foods? Do you feel more energetic and motivated mid-cycle?

It’s normal. The menstrual cycle involves hormonal changes that can impact blood glucose levels and insulin needs. Consequently, this becomes a significant variable for glucose levels in women. But how exactly does the menstrual cycle affect glucose?

We experience menstruation every month for much of our lives, but what is actually happening in our bodies?

What really happens during the menstrual cycle?

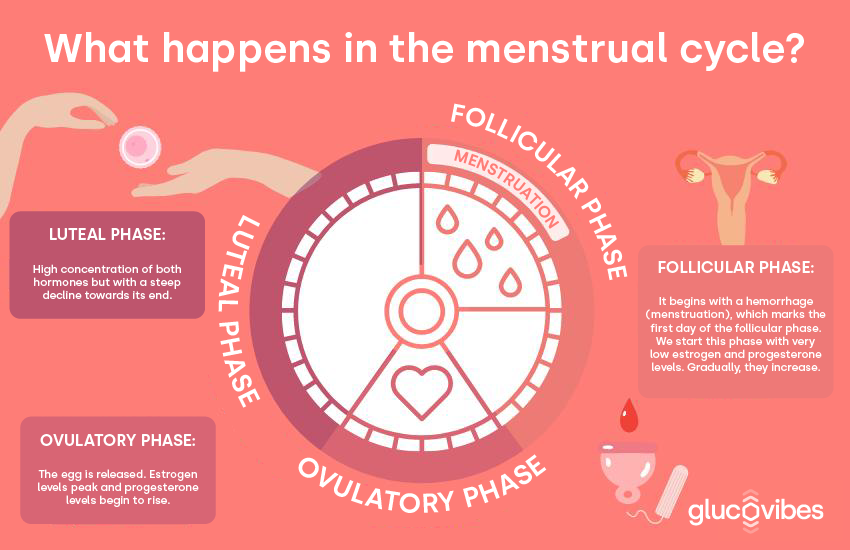

The menstrual cycle lasts from menarche (the first bleeding) to menopause. Each cycle typically lasts about 28 days and is divided into several phases: the follicular phase (approximately 14 days) and the luteal phase (around 13 days). These numbers can vary widely from person to person. Menstrual bleeding is an external symptom of a woman’s cyclicity and occurs at the end of the luteal phase and the beginning of the follicular phase. Each bleeding episode lasts between 3-6 days, with a loss of about 30-50 ml of blood. The human menstrual cycle is also characterized by a cyclic pattern of hormonal changes. The hormones produced by the ovaries are primarily responsible for the effects of menstruation, with the most significant ones being estrogen and progesterone (1), which have a major impact on the normal functioning of our body.

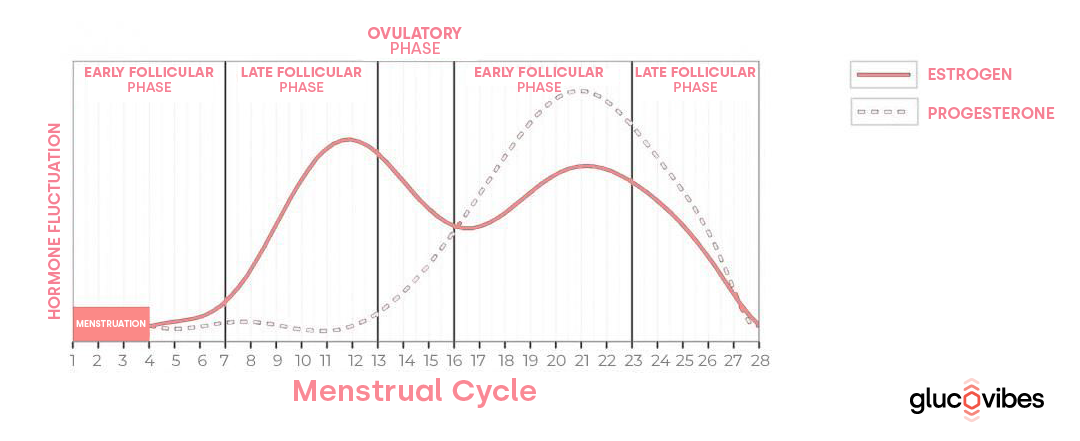

The menstrual cycle begins with bleeding (menstruation), marking the first day of the follicular phase. At the start of the follicular phase, estrogen and progesterone levels are very low. Consequently, the upper layers of the endometrium break down and shed, resulting in menstruation. As this phase progresses, estrogen levels increase.

During the ovulatory phase, there is a rise in luteinizing hormone concentrations, which triggers the release of the egg. Estrogen levels peak, and progesterone levels begin to rise.

Finally, in the luteal phase, hormone levels decline. The follicle that released the egg closes and forms the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. For most of this phase, estrogen levels are high, but progesterone levels are even higher. If the egg is not fertilized, the corpus luteum degenerates and stops producing progesterone, estrogen levels drop, and menstruation begins, marking the start of a new cycle.

How do menstruation (hormonal level changes) affect blood glucose and performance?

Hormones like estrogen and progesterone fluctuate predictably throughout the menstrual cycle. Beyond their reproductive functions, these hormones influence various physiological systems, and their effects on daily activities and exercise can impact performance.

What does each hormone do?

Estrogen: Promotes increased sensitivity of cells to insulin and enhances glycogen storage. Thus, during the follicular phase when estrogen levels are higher, blood glucose levels tend to decrease.

Progesterone: Promotes insulin resistance, meaning it makes it harder for cells to use glucose. Consequently, during the luteal phase when progesterone levels rise, blood glucose levels tend to increase.

💡 During days 10-13 of the cycle, when estrogen levels are higher, you might feel more energetic and stronger. Conversely, during days 20-25, with elevated progesterone, you may feel more fatigued and less energetic.

So, blood glucose levels can be elevated a week before menstruation, while at the start of the period, levels may be lower (2). Therefore, estrogen promotes glucose uptake stimulated by contraction during short-duration exercise, which should be beneficial for performance in higher-intensity aerobic exercises (3). The increase in estrogen relative to progesterone can determine the influence of ovarian hormones during the luteal phase. Consequently, these hormones can variably affect glycogen storage and plasma glucose levels during exercise (4).

How to improve my glucose control during menstruation?

Hormonal changes can lead to increased hunger and cravings for specific foods, particularly those high in carbohydrates and fats, which can result in higher glucose levels—especially in the days leading up to menstruation. During these days, levels of the hormones progesterone and estrogen in the blood decrease. Lower levels of progesterone and estrogen also lead to a drop in serotonin levels in the brain. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter, plays a key role in regulating mood and is often referred to as the “happiness hormone.” A deficiency in serotonin not only affects mood but also increases cravings for carbohydrate-rich foods like chocolate, cookies, and pastries.

Do you feel like you could eat everything in your fridge during your period? DON’T WORRY, it’s normal.

But how can you manage cravings and improve your glucose levels?

- Consume fiber-rich foods: Include fruits, vegetables, legumes, seeds, nuts, and whole grains in your diet, as they increase satiety.

- Stay active throughout the day: Engage in physical activity, run errands on foot, etc. Exercise stimulates the body and helps balance your glucose levels.

- Stay hydrated: Drink plenty of water throughout the day.

- Include a source of protein in every meal: Foods like meat, fish, eggs, dairy products, cheese, tofu, and seitan can help you feel fuller for longer.

- Get adequate rest: Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep each night.

💡 Hormonal fluctuations can lead to increased hunger and cravings for carbohydrate-rich foods. To better control your glucose levels, it is important to consume fiber-rich foods, include protein sources, stay hydrated, and remain active.

Levels of female hormones (progesterone and estrogen) fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle, affecting glucose levels, performance, and mood. When estrogen levels are higher, particularly around days 10-13 of the cycle, you might feel more energetic and stronger during exercise due to improved insulin sensitivity. Conversely, during days 20-25 of the cycle, when progesterone levels are elevated, you might feel more tired and less energetic, affecting both exercise and daily activities.

References

- [1] Messinis IE, Messini CI, Dafopoulos K. Novel aspects of the endocrinology of the menstrual cycle. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28(6):714–22.

- [2] Escalante Pulido JM, Alpizar Salazar M. Changes in insulin sensitivity, secretion and glucose effectiveness during menstrual cycle. Arch Med Res.1999;30(1):19–22.

- [3] Campbell SE, Febbraio MA. Effect of the ovarian hormones on GLUT4 expression and contraction-stimulated glucose uptake. Am J Physiol 2002; 282: E1139-46

- [4] Oosthuyse T, Bosch AN. The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise metabolism: implications for exercise performance in eumenorrheic women. Sports Med. 2010;40(3):207-27.