The big myth about vegetarian diets

‘And, you really don’t eat any meat?’ ‘Surely you must be low in iron.’ ‘No fish, either?’ ‘With a good steak… you’d change your mind!’ If you follow a vegetarian diet, it’s very likely you’ve heard these comments at some point. The belief that diets based on plant foods and some animal products are deficient in nutrients is widespread, but it’s far from the truth. Today, we debunk the big myth about vegetarian diets and explain how they can be just as healthy as diets that include meat and fish.

Nowadays, the main nutritional issues (which can occur in any diet) are more related to excessive consumption of added sugars, salt, and poor-quality fats than to nutrient deficiencies (1).

Today, we want to explain where you can find the nutrients that have been most scrutinized in vegetarian diets and which is the only nutrient you should consider supplementing.

The big myth about vegetarian diets is that they are deficient in essential nutrients… and that’s not true.

Proteins

‘Where do vegetarians get their protein?’ It’s the million-dollar question, and the answer is quite simple: from the fruits, vegetables, grains, and legumes that make up their diet. It has long been believed that plant-based foods lack high-quality protein because they are deficient in one or more essential amino acids. The reality is different:

- There are plant-based foods that contain all these necessary amino acids and are thus considered complete proteins, such as chickpeas, quinoa, soy and its derivatives, pistachios, and some seeds like chia and hemp.

- We can achieve complete protein by combining certain foods throughout the day. For instance, since most grains and seeds are deficient in lysine and legumes and nuts are generally deficient in methionine but rich in lysine, combining them together provides a complete protein (2).

Iron

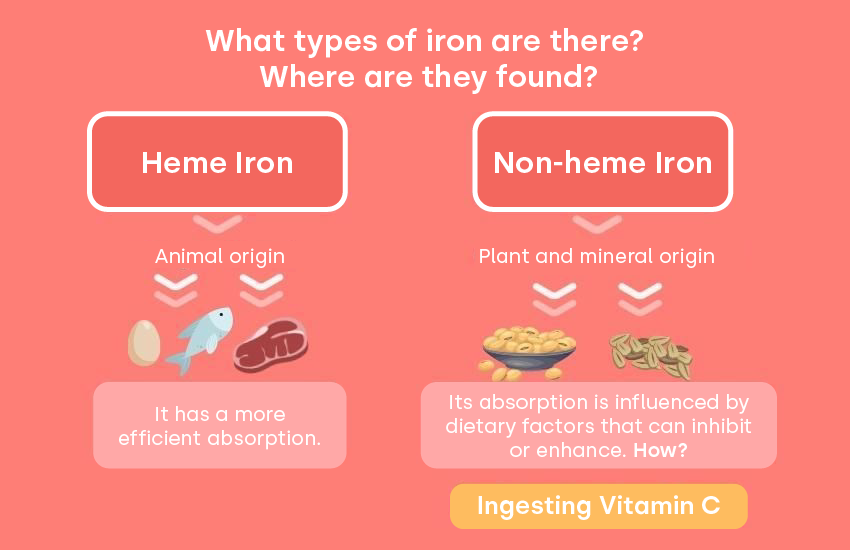

Iron can be found in two forms: heme and non-heme. Heme iron, which is more efficiently absorbed, is present only in animal-derived foods, while non-heme iron is the type found in plant-based foods. Thus, vegetarians obtain their iron from non-heme sources. It’s important to note that the absorption of non-heme iron can be influenced by dietary factors that either inhibit or enhance its uptake, which is crucial when planning your meals (1).

So, where can you find iron in plant-based foods? Legumes such as soybeans, white beans, lentils, and chickpeas are excellent sources. Additionally, cereals like quinoa, amaranth, and oats also provide significant amounts of iron (3).

How can you improve the absorption of non-heme iron? Vitamin C, found in fruits like strawberries, kiwi, and oranges, as well as in certain vegetables such as bell peppers, enhances iron absorption. On the other hand, calcium (abundant in dairy products), whole grains, and polyphenols from tea or cocoa are potent inhibitors of iron absorption (1).

Calcium

This mineral typically doesn’t pose problems for ovo-lacto vegetarians (those who consume eggs and dairy) since dairy products are a primary source of calcium. However, strict vegetarians should pay more attention.

It is advisable for plant-based milk options to be fortified with calcium; there are many choices available, including soy, oat, and rice milk. Other plant-based sources rich in calcium include tahini (sesame paste), almonds, soybeans, hazelnuts, and green leafy vegetables like spinach and Swiss chard (3).

Vitamin D

Vitamin D, along with calcium, plays a crucial role in bone health. While it’s true that the primary dietary source of vitamin D comes from animal products, it is not the only source. In fact, the main way to obtain this vitamin is through skin synthesis via solar radiation. Several factors can interfere with the synthesis of this vitamin, such as the season, exposure time, latitude, skin pigmentation (darker skin synthesizes less vitamin D), and the use of sun protection, which can also reduce vitamin D synthesis (1,5). (However, sun protection is absolutely necessary when exposed to solar radiation.)

For vegetarians, it is beneficial to consume fortified foods such as plant-based milk and breakfast cereals and to ensure adequate sun exposure. About 10-15 minutes of daily sun exposure is usually sufficient, while avoiding peak sun hours (between 12 p.m. and 5 p.m.). If adequate sun exposure is not possible, supplementing with vitamin D may be advisable (4).

💡 10-15 minutes of daily sun exposure is usually sufficient.

Omega 3

In general, the intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is typically high in vegetarian diets, while saturated fatty acids (SFAs) are present in lower amounts. However, the most common PUFAs in vegetarian diets are those from the omega-6 series, whereas omega-3 fatty acids are often deficient. This can be a concern, but there’s no need to worry—Glucovibes offers a solution (1).

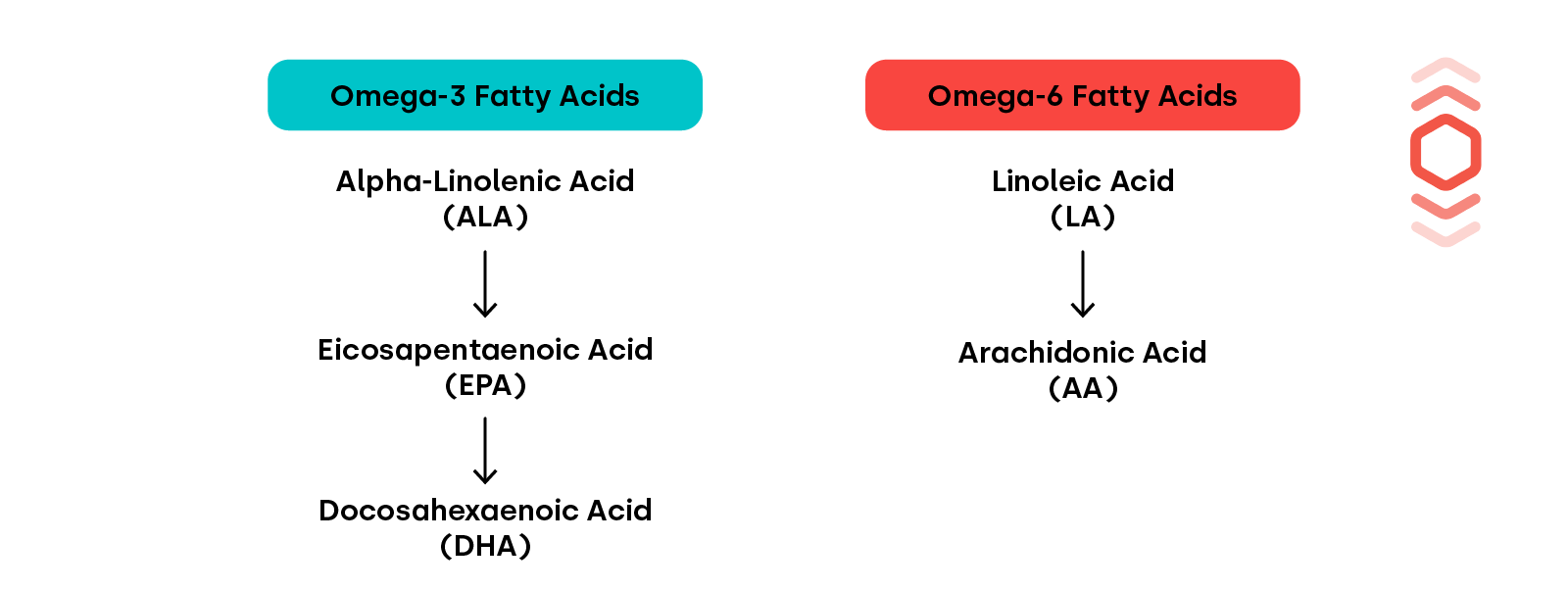

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is an omega-3 fatty acid and a precursor to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The primary sources of omega-3 EPA and DHA are fatty fish, though small amounts may also be found in fortified dairy products and eggs. Therefore, vegetarian diets often lack sufficient EPA and DHA, which are crucial for neurological and cardiovascular functions, among others (1).

However, our body is capable of converting ALA, present in various plant-based foods, into EPA and DHA, albeit in small amounts. Walnuts, chia seeds, and flaxseeds, for example, are good sources of ALA (1).

Vitamin B12

The deficiency of this vitamin is the most common among people who do not consume animal products, and its lack can lead to neuropsychiatric disorders and megaloblastic anemia. It’s important to distinguish that this type of anemia occurs due to a deficiency of both vitamin B12 and folic acid (B9), and not due to iron deficiency as seen in iron-deficiency anemia (5).

Supplementing with this micronutrient should be mandatory, even for ovo-lacto vegetarians, as it is very difficult to meet the recommended daily amounts with just the consumption of eggs and dairy products (5).

The human body cannot synthesize vitamin B12, so it must be obtained through diet, specifically from animal products. However, animals themselves do not synthesize B12; the vitamin is present in the microorganisms found in natural pastures (1).

This means that animals do not have B12 in their muscles directly, but rather the pastures they graze on contain this vitamin. Most of the meat we consume comes from animals raised in industrial farms, which do not graze freely but are fed with feed fortified with B12. Considering this, we could say that everyone is supplemented with B12, either directly (vegetarians who take supplements) or indirectly (non-vegetarians who consume supermarket meat).

For those following a vegetarian diet, the best way to supplement is with 2500 µg of cyanocobalamin once a week, as it is the most studied form and the easiest to find (6).

How healthy your diet is depends less on whether it includes meat and more on the balance of macronutrients you consume.

A well-planned vegetarian diet can be perfectly complete and suitable for all stages of life. In fact, because they are rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts, vegetarian diets can help reduce risk factors related to chronic diseases, such as lipid profiles and blood glucose levels (1).

At Glucovibes, we specialize in personalizing each user’s nutrition plan. We consider dietary preferences, lifestyle, possibilities, personal factors, diseases, and life situations when organizing their nutritional plan. Start taking care of your metabolic health today and discover how a vegetarian diet can be just as healthy, if not healthier, than any other.

References

- [1] García E, Gallego A, Vaquero P. ¿Son las dietas vegetarianas nutricionalmente adecuadas? Una revisión de la evidencia científica. Nutrición hospitalaria. 2019;36(4):950-961.

- [2] González M. Dietas vegetarianas. Offarm. 2005;24(5):82-90.

- [3] Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos (BEDCA). [En línea]. [citado 2022 marzo 16]. Disponible en: http://www.bedca.net/bdpub/index.php.

- [4] Craig W, Mangels AR. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. American dietetic association. 2009;109(7):1266-1282.

- [5] Martínez L. B12: absorción, tipos y suplementación en vegetarianos[Internet]. Alimenta .2015 [ citado 2022 marzo 16]. Disponible en: https://www.dietistasnutricionistas.es/b12-absorcion-tipos-y-suplementacion-en-vegetarianos-3a-parte/

- [6] Buil M, Bobé F, Allué A, Trubat G. Vitamina B12 y dieta vegetariana. Semergen. 2009;35(8):412-414.